Mass, weight, and force. The mass M of an object is a measure of the amount of matter it contains and will be constant, since it depends on the number of constituent molecules and their masses. On the other hand, the weight w of the object is the gravitational force on it, and is equal to Mg, where g is the local gravitational acceleration. Mostly, we shall be discussing phenomena occurring at the surface of the earth, where g is approximately 32.174 ft/s2 = 9.807 m/s2 = 980.7 cm/s2. For much of this book, these values are simply taken as 32.2, 9.81, and 981, respectively.

Newton’s second law of motion states that a force F applied to a mass M will give it an acceleration a:

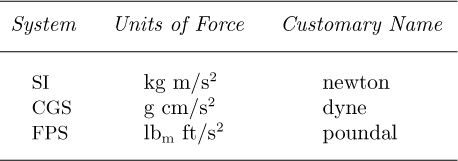

from which is apparent that force has dimensions ML/T2. Table 1.7 gives the corresponding units of force in the SI (meter/kilogram/second), CGS (centimeter/gram/second), and FPS (foot/pound/second) systems.

Table 1.7 Representative Units of Force

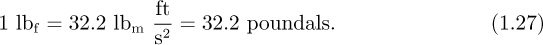

The poundal is now an archaic unit, hardly ever used. Instead, the pound force, lbf, is much more common in the English system; it is defined as the gravitational force on 1 lbm, which, if left to fall freely, will do so with an acceleration of 32.2 ft/s2. Hence:

When using lbf in the ft, lbm, s (FPS) system, the following conversion factor, commonly called “gc,” will almost invariably be needed:

Some writers incorporate gc into their equations, but this approach may be confusing since it virtually implies that one particular set of units is being used, and hence tends to rob the equations of their generality. Why not, for example, also incorporate the conversion factor of 144 in2/ft2 into equations where pressure is expressed in lbf/in2? We prefer to omit all conversion factors in equations, and introduce them only as needed in evaluating expressions numerically. If the reader is in any doubt, units should always be checked when performing calculations.

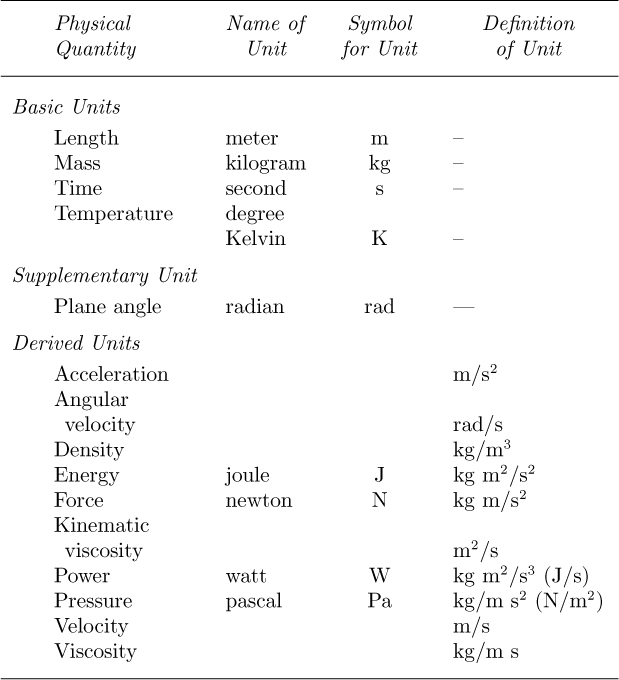

SI Units. The most systematically developed and universally accepted set of units occurs in the SI units or Système International d’Unités6; the subset we mainly need is shown in Table 1.8.

6 For an excellent discussion, on which Tables 1.8 and 1.9 are based, see Metrication in Scientific Journals, published by The Royal Society, London, 1968.

Table 1.8 SI Units

The basic units are again the meter, kilogram, and second (m, kg, and s); from these, certain derived units can also be obtained. Force (kg m/s2) has already been discussed; energy is the product of force and length; power amounts to energy per unit time; surface tension is energy per unit area or force per unit length, and so on. Some of the units have names, and these, together with their abbreviations, are also given in Table 1.8.

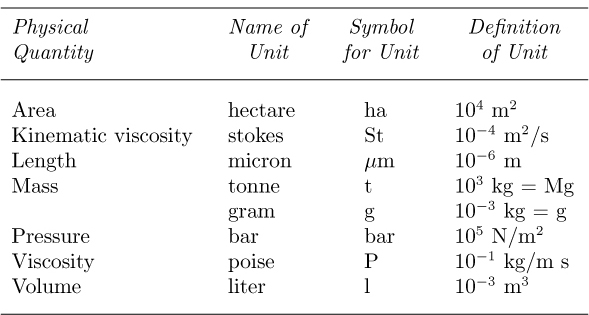

Tradition dies hard, and certain other “metric” units are so well established that they may be used as auxiliary units; these are shown in Table 1.9. The gram is the classic example. Note that the basic SI unit of mass (kg) is even represented in terms of the gram, and has not yet been given a name of its own!

Table 1.9 Auxiliary Units Allowed in Conjunction with SI Units

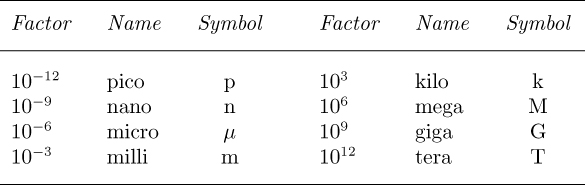

Table 1.10 shows some of the acceptable prefixes that can be used for accommodating both small and large quantities. For example, to avoid an excessive number of decimal places, 0.000001 s is normally better expressed as 1 μs (one microsecond). Note also, for example, that 1 μkg should be written as 1 mg—one prefix being better than two.

Table 1.10 Prefixes for Fractions and Multiples

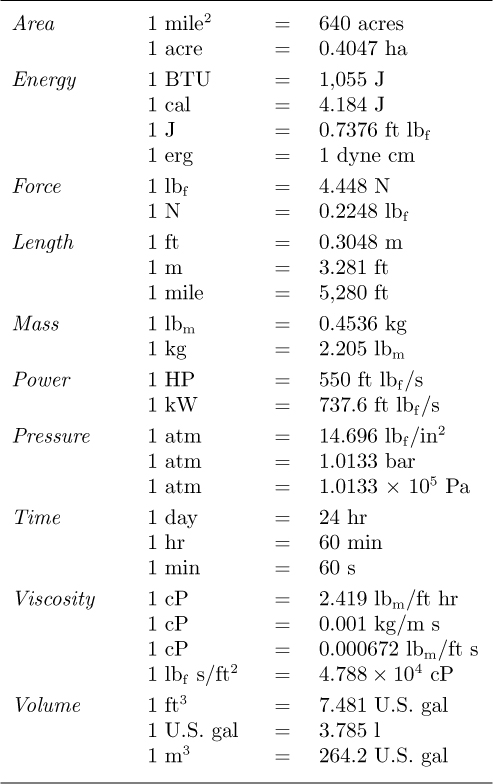

Some of the more frequently used conversion factors are given in Table 1.11.

Table 1.11 Commonly Used Conversion Factors

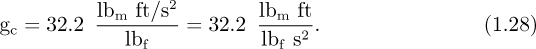

Part 1. Express 65 mph in (a) ft/s, and (b) m/s.

Solution

The solution is obtained by employing conversion factors taken from Table 1.11:

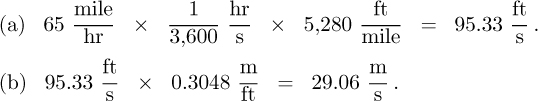

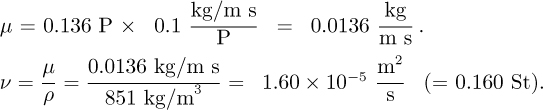

Part 2. The density of 35 °API crude oil is 53.1 lbm/ft3 at 68 °F and its viscosity is 32.8 lbm/ft hr. What are its density, viscosity, and kinematic viscosity in SI units?

Solution

Or, converting to SI units, noting that P is the symbol for poise, and evaluating ν:

Example 1.2—Mass of Air in a Room

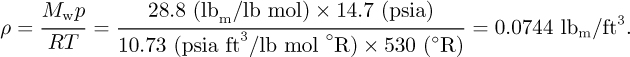

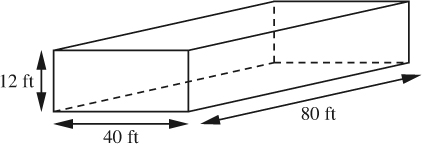

Estimate the mass of air in your classroom, which is 80 ft wide, 40 ft deep, and 12 ft high. The gas constant is R = 10.73 psia ft3/lb-mol °R.

Solution

The volume of the classroom, shown in Fig. E1.2, is:

V = 80 × 40 × 12 = 3.84 × 104 ft3.

Fig. E1.2 Assumed dimensions of classroom.

If the air is approximately 20% oxygen and 80% nitrogen, its mean molecular weight is Mw = 0.8 × 28 + 0.2 × 32 = 28.8 lbm/lb-mol. From the gas law, assuming an absolute pressure of p = 14.7 psia and a temperature of 70 °F = 530 °R, the density is:

Hence, the mass of air is:

M = ρV = 0.0744 (lbm/ft3) × 3.84 × 104 (ft3) = 2, 860 lbm.

Leave a Reply