Lake Michigan—unsalted and shark-free.

A.1 Useful Integrals in Chemical Reactor Design

Also see www.integrals.com.

ɛɛɛ

ɛɛɛ

ɛɛɛ

ɛɛɛɛɛ

where p and q are the roots of the equation.

A.2 Equal-Area Graphical Differentiation

There are many ways of differentiating numerical and graphical data (cf. Chapter 7). We shall confine our discussions to the technique of equal-area differentiation. In the procedure delineated here, we want to find the derivative of y with respect to x.

This method finds use in Chapter 5.

- Tabulate the (yi, xi) observations as shown in Table A-1.

- For each interval, calculate Δxn = xn – xn-1 and Δyn – yn – yn-1.TABLE A-1 FINDING DIFFERENTIALS FROM DISCRETE DATAxiyiΔxΔyx1y1x2 – x1y2 – y1x2y2x3 – x2y3 – y2x3y3x4y4and so on.

- Calculate Δyn/Δxn as an estimate of the average slope in an interval xn-1 to xn.

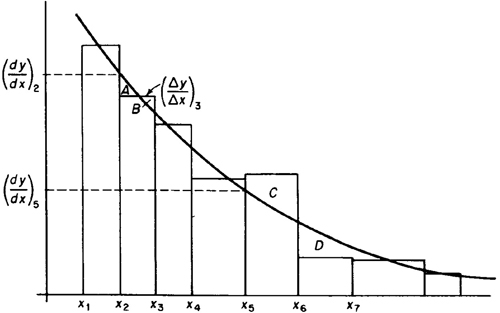

- Plot these values as a histogram versus xi. The value between x2 and x3, for example, is (y3 – y2)/(x3 – x2). Refer to Figure A-1.

Figure A-1 Equal-area differentiation.

Figure A-1 Equal-area differentiation. - Next, draw in the smooth curve that best approximates the area under the histogram. That is, attempt in each interval to balance areas such as those labeled A and B, but when this approximation is not possible, balance out over several intervals (as for the areas labeled C and D). From our definitions of Δx and Δy, we know thatThe equal-area method attempts to estimate dy/dx so thatthat is, so that the area under Δy/Δx is the same as that under dy/dx, everywhere possible.

- Read estimates of dy/dx from this curve at the data points x1, x2, … and complete the table.

An example illustrating the technique is given on the CRE Web site, Appendix A.

Differentiation is, at best, less accurate than integration. This method also clearly indicates bad data and allows for compensation of such data. Differentiation is only valid, however, when the data are presumed to differentiate smoothly, as in rate-data analysis and the interpretation of transient diffusion data.

A.3 Solutions to Differential Equations

A.3.A First-Order Ordinary Differential Equations

See the CRE Web site, Appendix A.3.

Using integrating factor = exp , the solution is

Example A–1 Integrating Factor for Series Reactions

Comparing the earlier equation with Equation (A-15) we note

f(t) = k2

and the integrating factor

Multiplying both sides by the integrating factor

Integrating

A.3.B Coupled Differential Equations

Techniques to solve coupled first-order linear ODEs such as

are given in Web Appendix A.3 on the CRE Web site (http://www.umich.edu/~elements/6e/appendix/AppA.3_Web.pdf).

A.3.C Second-Order Ordinary Differential Equations

Methods of solving differential equations of the type

β

can be found in such texts as Applied Differential Equations by M. R. Spiegel (Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson, 1958, Chapter 4; a great book even though it’s old) or in Differential Equations by F. Ayres (New York: Schaum Outline Series, McGraw-Hill, 1952). Solutions of this type are required in Chapter 15. One method of solution is to determine the characteristic roots of

which are

The solution to the differential equation is

where A1 and B1 are arbitrary constants of integration. It can be verified that Equation (A-18) can be arranged in the form

Equation (A-19) is the more useful form of the solution when it comes to evaluating the constants A and B because sinh(0) = 0 and cosh(0) = 1.0.

A.4 Numerical Evaluation of Integrals

In this section, we discuss techniques for numerically evaluating integrals for solving first-order differential equations.

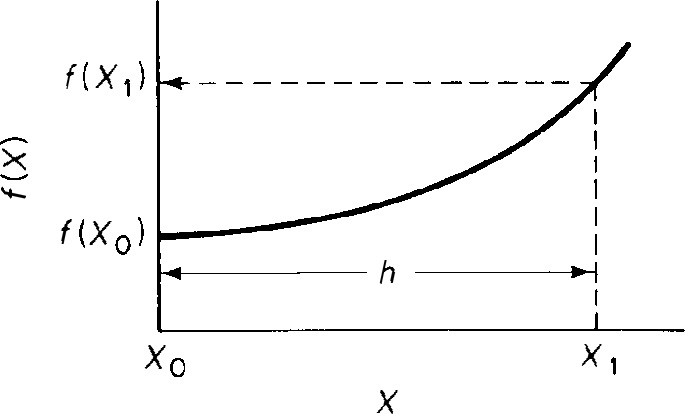

- Trapezoidal rule (two-point) (Figure A-2). This method is one of the simplest and most approximate, as it uses the integrand evaluated at the limits of integration to evaluate the integralwhen h = X1 = X0.

Figure A-2 Trapezoidal rule illustration.

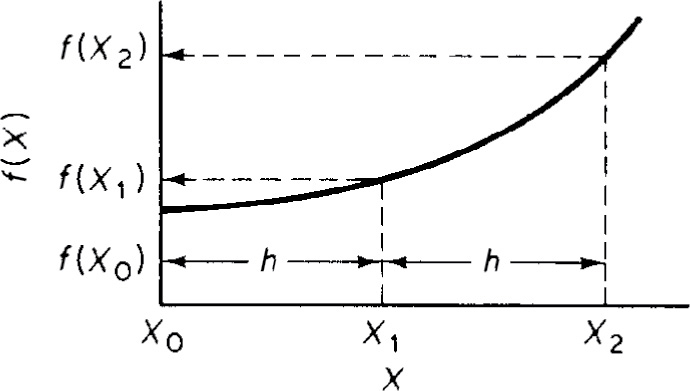

Figure A-2 Trapezoidal rule illustration. - Simpson’s one-third rule (three-point) (Figure A-3). A more accurate evaluation of the integral can be found with the application of Simpson’s rule:whereMethods to solvein Chapters 2, 4, 5, 12, and in Chapter 17

Figure A-3 Simpson’s three-point rule illustration.

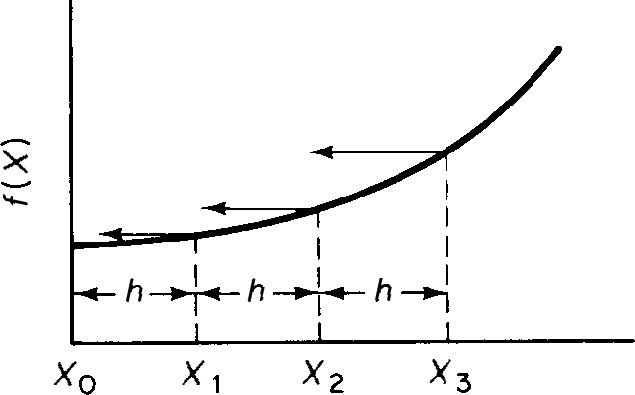

Figure A-3 Simpson’s three-point rule illustration. - Simpson’s three-eighths rule (four-point) (Figure A-4). An improved version of Simpson’s one-third rule can be made by applying Simpson’s three-eighths rule:where

Figure A-4 Simpson’s four-point rule illustration.

Figure A-4 Simpson’s four-point rule illustration. - Five-point quadrature formula.where

- For N = 1 points, where (N/3) is an integerwhere

- For N = 1 points, where N is evenwhere

These formulas are useful in illustrating how the reaction engineering integrals and coupled ODEs (ordinary differential equation(s)) can be solved, and also when there is an ODE solver power failure or some other malfunction.

A.5 Semi-Log Graphs

Review how to take slopes on semi-log graphs on the Web. Also see https://bolide.cs.uoguelph.ca/tutorials/GLP. Also see Web Appendix A.5, Using Semi-Log Plots for Data Analysis.

A.6 Software Packages

Instructions on how to use Polymath, MATLAB, Python, Wolfram, COMSOL, and Aspen can be found on the CRE Web site.

Leave a Reply